DOJ used secret court orders in Seattle, forcibly obtaining private information related to 2020 protests

The Inspector General of the US Department of Justice (DOJ) released a report last month, highlighting how the DOJ used secret orders to obtain otherwise private information from the accounts of journalists, congressional staffers, and members of Congress during Trump’s first term as President.

The same type of secret orders the DOJ used in Washington D.C. were also used in Seattle related to the Black Lives Matter demonstrations in 2020. These “2703(d) orders” allow federal law enforcement to obtain wide-ranging personal data without probable cause of criminal activity. Normally warrants require suspicion of criminal activity under the Fourth Amendment. The DOJ declined to say who or what was targeted, as well as what specific information was obtained through the use of these orders in Seattle.

With a second Trump presidency staring Americans in the face, and MAGA’s propensity to label many Americans “terrorists” merely for expressing protected speech they disagree with, 2703(d) orders pose implications for data privacy and First Amendment rights. Anyone who attends protests or other assemblies the government and police deem criminal or anyone the government thinks might be “relevant” to a criminal investigation, could conceivably be targeted under the 2703(d) process.

As the 2020 protests developed, the Seattle Police Department (SPD) expanded coordination with federal law enforcement, creating a massive task force to investigate acts of looting, theft, and arson among other targets. By August 2020, the task force ballooned to 71 officers between the ATF, FBI, Bellevue Police Department, and SPD.

Former SPD Assistant Chief of the Investigations Bureau, Deanna Nolette, wrote to former SPD Chief Carmen Best that “We are going to take any cases we can federal.”

At the federal level, discussions of using secret data collection orders immediately surfaced at the highest echelon of the US Attorney’s Office in Seattle.

On June 2, 2020, an Assistant US Attorney (AUSA) in Seattle, Todd Greenberg, emailed King County Senior Prosecuting Attorney Gary Ernsdorff, raising the proposition of using secretive “2703(d)” orders to obtain “various types of information related to email and social media accounts.”

These orders, reviewed and approved by a federal judge under 18 U.S.C. §2703, do not require probable cause of criminal activity, the legal threshold required to obtain a warrant under the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution.

Greenberg wrote to Ernsdorff that the legal threshold for a §2703(d) order is well below the probable cause threshold, merely requiring “that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the records or other information sought are relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.”

Saying that the reasonable grounds for a §2703(d) order could be pled by a US Attorney, Greenberg went on, writing that any order would not need a sworn affidavit by a federal law enforcement agent, which is typically required to obtain a warrant.

The nature of data obtained through a §2703(d) order can poison a criminal prosecution, miring an entire chain of evidence within the swamp of data collection without probable cause of criminal activity. Under the “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine, evidence obtained without a warrant in a criminal prosecution may be inadmissible in court.

Using personal electronic data obtained without a warrant and without probable cause would “prove to be fatal in state court,” according to Ernsdorff.

After Ernsdorff’s appraisal, Greenberg wrote that he considered using §2703(d) orders in King County “a no-go,” although he argued that the silver platter doctrine “can work where there is a true bright-line division between state and federal” law enforcement.

Ernsdorff replied to Greenberg that he had never seen the “silver platter doctrine” successfully used, writing, “it requires the information to be gathered lawfully by federal agents with the sole intent of pursuing a federal case. Without any state involvement whatsoever.”

In another email, Greenberg wrote, “I am more than happy to use federal legal process quickly and broadly, but we also need to be mindful of how we obtain evidence federally and whether that evidence will be usable in state criminal cases/investigations.”

HardPressed posed the question directly to the US Attorney’s Office in the Western District of Washington, in Seattle, asking if the DOJ used §2703(d) orders to obtain information related to any 2020 protest investigations. Emily Langlie, a spokesperson for the office, responded yes.

“Two AUSA who handled downtown disorder cases reviewed their work and determined that two requests for records were made using 2703(d) – there was one request in each of two cases, to a service provider for subscriber information,” wrote Langlie. “That information was then used to get a court authorized search warrant for information from that same service provider regarding the accounts in question.”

HardPressed asked for the status of each of these two cases. Langlie responded that she could not provide further information.

Casey McNerthney, a spokesperson for the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office (KCPAO) told HardPressed in an email that the two cases where the US Attorney’s Office in Seattle used §2703(d) orders likely did not involve the KCPAO, but that he could not definitively confirm that.

[Update 1/7/25 - McNerthney responded via email, stating that after conversing with the U.S. Attorney’s Office Western District of Washington in Seattle, he "confirmed the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office was not involved with the two cases related to the 2020 protests and §2703(d) orders."]

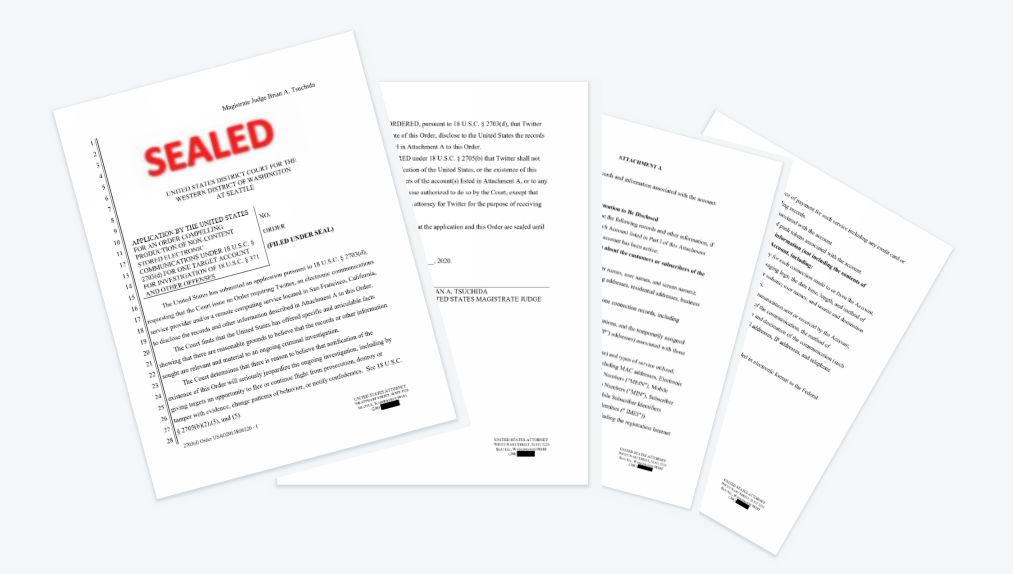

Sample §2703(d) Order

While proposing to use §2703(d) order data collection, Greenberg sent a sample order, a request for Twitter subscriber information, to Ernsdorff for review. Filed in secret, under seal, the order also legally prohibits Twitter (now X) from notifying anyone, including the target of the order, that their account data is being requested by Federal law enforcement.

The sample order includes an expansive dragnet of subscriber information, including emails, physical addresses, IP addresses, session dates and times, cell data including MAC, IMEI and other mobile device identification numbers, payment information, phonebook, Apple push tokens associated with the account, and messaging logs. Also included in the order is the IP and account data associated with every single other account that the target account has communicated with.

While wide ranging data can be obtained by federal law enforcement under a §2703(d) order, the content of the communications at hand cannot be forcibly compelled through a §2703(d) order. That requires a warrant. However, as seen in Seattle, a §2703(d) order can be used as a stepping stone to a warrant in the future.

HardPressed contacted Meta, X, and Bluesky to ask what their policies were in responding to §2703(d) orders, but none replied in time for publication. SPD has also not responded to multiple requests for comment.

The full sample 2703(d) order is included below: